I thought of being forced to witness the unnatural revels of a diabolical feast, of seeing the rotting flesh distributed, of drinking the dead corrupted blood, of hearing the anthems of fiends howled in insult, on that awful verge where life and eternity mingle, of hearing the hallelujahs of the choir, echoed even through the vaults, where demons were yelling the black mass of their infernal Sabbath.

— Charles Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer (1820)

Over the past several months, I had been exchanging social media drive-bys with John Garrad, who has been doing some academic work on the representation of the gothic in games. He shared some slides of his work in progress on Twitter, which I thought was interesting, so we talked a little further, and he agreed to let me share some of the contents of that conversation.

Slideshow available at https://t.co/HoGwLJsJC7 ; those of you not at #RG18 can click along at home!

— Jon Garrad has finally thought of a username (@propergoffick) October 27, 2018

Gothic-Punk: do you see it as an evolution of a wider, long-term Gothic tradition, or a product of the 1990s cultural circumstances, or as a collection of what the developers over time have deemed relevant to the project, or… something else that I haven’t thought of?

Part of Vampire’s longevity, in either Masquerade or Requiem formats, is that the gothic trappings it affects are tied to an emotion rather than an era. Vampire wouldn’t have survived long if it was quintessentially 80s or 90s. (You can see a parallel evolution here in technology, in that V20, released in 2011, doesn’t bother to account for the prevalence of smartphones or of wide-scale surveillance, either of which would pose massive Masquerade threats. We just handwaved them away.)

While the early material deliberately attached itself to a specific subculture, social scene, and music expression, it slowly pulled itself away from those over the progression of developers, with the intent of opening itself up to a greater breadth of players. Even through that extrication of itself from a defined “scene,” it kept the literary component of the gothic movement throughout because, again, those transcend decade. I don’t know if it’s still out there, but I recall one of my style guides that hammered on the point “gothic, not goth.”

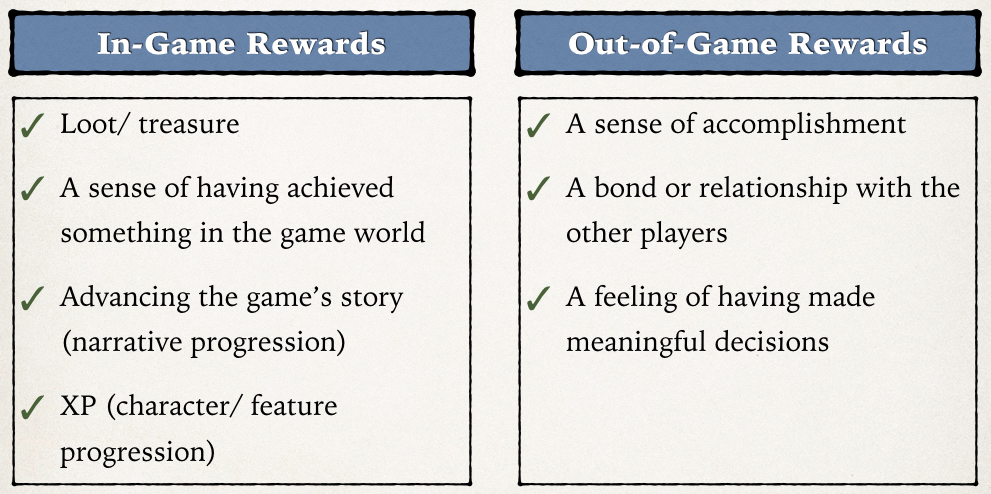

The big one on this front: how do you feel VtM goes about making its Gothic credentials concrete and real to players? I’m particularly interested in mechanics here — which aspects of the game create a Gothic ‘feel’ when people are sat down playing.

The big three for me:

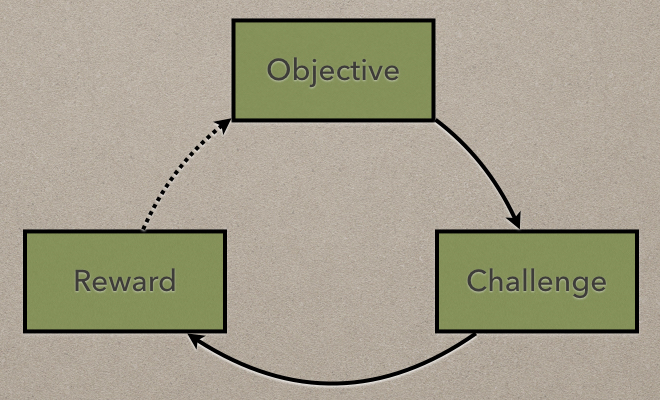

Game Structure: The game was built in literary “units of play,” as opposed to the traditional RPG structures derived from wargames. We still had turns, just because they were atomic, but Vampire intended to wean storytellers away from tactical encounters and frame things more dramatically (whether literary or stage) in terms of things like scenes, chapters, and overall chronicles. The overarching story container was not a “campaign,” with its military-conquest connotations, but a chronicle, a record, a retelling of events that happened. And in so doing, it relied very heavily on unreliable narrators, so you were never sure you were getting a clinical accounting of events as much as you were getting a definitely biased perspective of events, unless you were there, and even if you were, you’re not unbiased yourself.

Cultural Touchpoints: Vampire heavily invoked western, Abrahamic traditions, akin to the gothic movement’s reliance on religious and feudal motifs to carry its themes of superstition and relative primitivism. It leaned on straight-up gothic notions of madness and romance (themselves not very progressive…) and gave systems for them in terms of things like Humanity, Derangements (sometimes incurable…), and maintaining distance in relationships. The classic image of vampire lovers feeding from each other is actually a peril in Vampire because it can create a blood bond, which has all of the outward appearances of love, but strips away the (religious alert!) Free Will of the lover to exercise choice when it comes to the beloved. All of this is great stuff and immediately transgressible for players who have felt marginalized, in whatever context or extent, by traditional societal expectations, and provides mechanics by which one can express that transgression.

In more than one case, Vampire had intended to “open things up,” but when it showed rather than told, those showings became the default rather than a single expression. For example, the Caine myth was intended originally to be a myth, but it quickly became the predominant myth (IMO because it was so relatable, and because it gave a religious structure that players could rebel against and be rewarded for so doing. Instead of degenerate priests and corrupt churches, Vampire makes the religious institution part of the origin story and encourages players to break from their obedient relationship to it.) The Prince and Primogen structure in Gary and Chicago were originally intended to be a political situation, but over time they became the political default. (Again, IMO, I think this is at least partially because it provides an example that storytellers can depart from as they will, as opposed to having to define their home chronicle whole cloth — which Requiem demanded.)

Supernatural Prevalance: This is obvious, but Vampire: The Masquerade wouldn’t have taken off if it was simply GOTH: THE VENDETTA. Giving players access to abilities beyond mortal ken isn’t just a game design call to action, it puts the tools of gothic literature into their hands. They’re the ones able to drop the helmet on Manfred’s son, they’re the ones able to call forth the children of the night, they’re the ones able to shroud men’s minds. And the framing isn’t “with great power comes great responsibility,” it’s “you are the monster,” and it expects some concomitant moral failure and abuse of those otherworldly powers in pursuit of selfish goals (which can themselves be regretted or indulged, back to the system above). Without powers, Vampire could have been Mad Men, with bitchy people doing awful but mundane things to one another. Instead, it’s a passion play on a deliberately lurid stage with an infinite special effects budget that flirts with the forbidden when engaged.

Did you strive for a different kind of Gothic with Revised? (I’ve been fascinated by the ST Vault submission guidelines, which really make plain the differences between the editions that I’ve always felt were there but never really articulated — and I wondered if any of the Revised development fed into the game’s genre positioning.)

I don’t know if it was a deliberate striving for a specific kind of gothic so much as it was an evolution. It became its own thing, with definite gothic influence, and true to itself. For my own part, I think this is a maturing and finding one’s own voice over the course of developing and writing the amount of books I did. I remember one of my earliest writing projects for school, which might as well have been a Lovecraft manuscript with a hasty find-and-replace, absolutely a pastiche, and early in Vampire, I was similarly attempting to copy influences. Over time, I thought it definitely took on its own voice, its own life. You can easily pick up a Vampire book and identify its gothic parentage, but on a more substantial reading and use, especially for the Revised and V20 material, you find that Vampire is consistent largely with Vampire, while still acknowledging and even revering the movement that helped it get there.

And finally: V5 aligns the Gothic-Punk with prior editions. I wondered if you had any insight about why that point was made, and if V5 is consciously trying to distance itself from something in the tradition?

On this one, I don’t feel qualified to render an opinion. By conscious choice, I haven’t been a part of V5, primarily because, as they’ve wanted to create a new envisioning of the game, I didn’t want to encumber that with assumptions that I carry, having developed and written for it for two decades. It’s others’ exercise to determine whether V5’s vision is an evolution for Vampire or simply another perspective on it, and whether that’s for better or worse, but none of my input is there. A different creative vision requires a different expression.