I like the Keep on the Borderlands. It’s a self-contained ecology of adventure gaming, good for new players to learn systems and substantial enough for experienced players to turn the knobs and pull the levers of the home base. Rules as written, the locations are diverse enough to give contrast, but not so broad that the location feels like a grab bag rather than a cohesive whole.

(I’m talking about B2 here, not the new boxed set, with which I have no experience.)

The region has a variety of calls to action, especially in the adventure category. The Caves of Chaos are perhaps the most recognizable feature and largest location, but other sites abound. The weird hermit can be played for menace, horror, or even comedy. The bandit camps make for a good law-vs.-chaos conflict, but can also add depth as an alternative “town” when the adventurers want to unload sketchy loot or hire retainers who might deliberately not have attachments to the settlement. The Cave of the Unknown provides GMs a chance to add their own unique location, and invites speculation as to its nature — why has no one nearby found this? Why is the forested area around it cleared of tress in the immediate proximity?

The titular keep is a compelling home base as well. Since it’s “on the Borderlands,” there’s a sense that the player characters have to rely on themselves and the other local residents, rather than depending on “authorities” to whom they can offload their problems. The keep is the last redoubt out here in the borderlands. The keep needs support.

The keep can also be a great cauldron of intrigue. The keep can be turned to the characters’ aims, should they be able to play its politics well. The Castellan has a purpose, but player characters can guide that purpose or they can run afoul of frontier law. It’s all emergent gameplay, and gives context to what the characters do. (And if the player characters don’t care about the politics of the keep, they miss out on nothing; there’s nothing wrong with the keep as a simple fallback and restock base for traditional adventure-exploration gameplay.)

With a bit of fiat, improv, or dice rolls, the various characters there can become an ensemble of motivators, antagonists, foils, and friends. While it definitely requires the GM to flex some creative muscle, the residents of the keep need not be defined by their jobs. Rather, looking at the keep’s facilities shows what resources the keep has to offer (and by comparison to what’s absent, what it can’t offer, and must be done without or quested-for). The people providing those goods and services have ample room to become fully fledged characters, or can remain stock individuals where useful.

Topics for Redevelopment

When I gamemaster, I run almost nothing “out of the box.” Like, I believe, most gamemasters, I like to tinker and kitbash a little bit to give specific context to the particular group of players with whom I’m playing. This makes every session or campaign feel unique and opens up avenues for player expression. If the adventurers want to redeem or punish the scurrilous cleric at the keep, I can emphasize those particular encounters. If they want to develop an unspoken quid pro quo with one of the Castellan’s advisors, I can shine more light there. If they decide to throw in with the more unsavory elements, or even work as proxies for the bandits outside the keep, that’s doable, too.

What I don’t personally enjoy is the idea of the adventuring party being a bunch of racially motivated smash-and-grabbers. Given both a desire for extra context and adopting a more compelling narrative reason for dealing with the Caves of Chaos than “go kill those Other people over there,” I lean more into a certain set of literary influences to reshape the experience when I run Keep on the Borderlands.

Adding Phantasmagoria, Dread, and Wonder

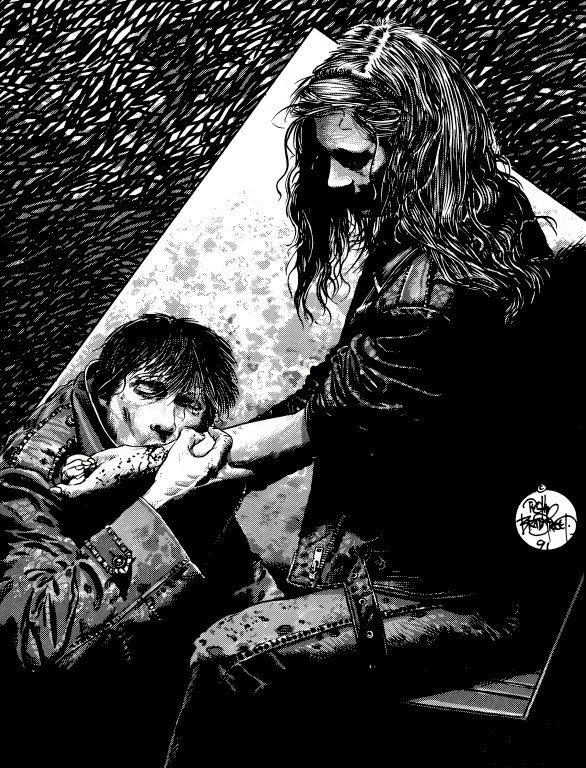

I make no secret of my preference for my fantasy gaming to have a tinge of the literary Gothic. Not (necessarily) to be all highfaluting and, well, literary, but because it comes with a set of aesthetics and themes that I think match well with lurid tales of the imagination. I don’t much enjoy “stock” fantasy; I like when there’s a sense of wonder and fear and enchantment that comes from exploring the edges of imagination. Thematically, I like inflecting my games with the strangeness of the unknown, superstition, morality, and the sublime. Imagine the adventurer standing on the precipice, almost subsumed by the full magnitude of the world’s truths!

Bringing that to The Keep on the Borderlands is a rewarding exercise in world-planning and game-running. Holding the horror of the Caves of Chaos at bay becomes a question of self-preservation, the intrusion of the terrible and the profane and fantastical.

The Castle of Otranto on the Borderlands

I borrow heavily from Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto when I run the Keep on the Borderlands. Sometimes I even call the keep itself “Otranto.” The pervasive sense of medievalism in Walpole’s book meshes well with medieval-themed roleplaying games, and some games’ mechanics (like Shadowdark‘s light-source scarcity rules or the danger-tinged magic of Outcast Silver Raiders) make for a good fit with those themes and aesthetics, making them experiential.

Specifics I lift:

- An enormous helmet has ominously fallen from the skies. This is a key element of The Castle of Otranto and it’s a great add to the keep. It creates a call to action to have someone trapped down there in perdition, whom the players’ characters can seek to aid, and it also gives an excuse to justify the revelation of a dungeon area beneath the keep proper (which can be as big or as small as necessary, based on the players’ interest). That means there’s a dungeon you don’t even have to leave town to explore, and you’re probably the first group of adventurers to do it.

- The Castellan is Manfred. Well, not Manfred proper, because Manfred’s a full-tilt jerk and there’s a not a lot of room to want to interact with him, but a descendant of Manfred, Castellan Manfredi. This also lets me lean into the familial guilt and horror aspect of the literary Gothic. If left to his or her own devices, Castellan Manfredi will surely reap some sort of familial doom, but if the players want to involve themselves with it, they can perhaps help terminate the family curse, or otherwise find themselves embroiled in the congenital saga.

- Paintings, portraits, and other inanimate objects that move or seem to move, giving the impression that the keep or some force within it is aware of the players’ characters and keeping an eye on them.

The Goblin Curse

Going back to the idea of elevating the characters from being racist thugs, I like to back away from the whole idea of having the occupants of the Caves of Chaos exist in terms of “race,” legacy, lineage, whatever. The useful aspect of having a site-based adventure locale is the call to action to explore that site and face its conflicts. What I want to set aside is the idea that they’re a “culpable people” or other sort of benighted “race” that must be cleansed. Man, even typing that is gross.

I’ve run the Keep on the Borderlands in the past with more esoteric thematics. Once, using Pathfinder, I reworked the Caves of Chaos to be the malfunctioning remains of a sort of multiplanar machine, and replaced the goblins with akatas and the other creatures with other “void” aberrations, making the place a site of cosmic horrors from beyond and their incursion into the game world. I’ve similarly used modrons when running Keep on the Borderlands in D&D, and made the Caves of Chaos a site of demonic infestation (which, honestly, felt more like Diablo than I wanted the experience to be).

I think my current favorite, though, is reworking what it is to be a goblin or other monster, as opposed to just replacing the monster types.

As handled in Mörk Borg, goblins occur when an existing goblin attacks a character: If the attacking goblin survives the encounter, the character attacked (whether or not the attack hits) turns into a goblin themselves. This is excellent — it creates an urgency for players to pursue goblins at risk to themselves, pulling them deeper into whatever’s going on. In some cases, you even have individuals bringing the goblin curse upon themselves, as a result of deranged cults or perilous rituals. It also frees the group from having to deal with things like “Do we murder all the combat-participant creatures and leave the children to be starving orphans in the caves?” I like this framing of monsters as baleful manifestations rather than inherently villainous peoples. Monsters are monsters because they’ve chosen to be monsters or otherwise run afoul of a monstrous world.

So what is the goblin curse? In all honesty, I think this is one of the mysteries best left unsolved. It makes the world scary. But that doesn’t mean the people in the world don’t have their own theories, and strange occultists surely try to turn the observable details of the curse to their own ends, making for some weird rituals — et voila, context for the “chaos temple” in the depths of the Caves of Chaos region, and possible origins for some of the other denizens of the deeps.